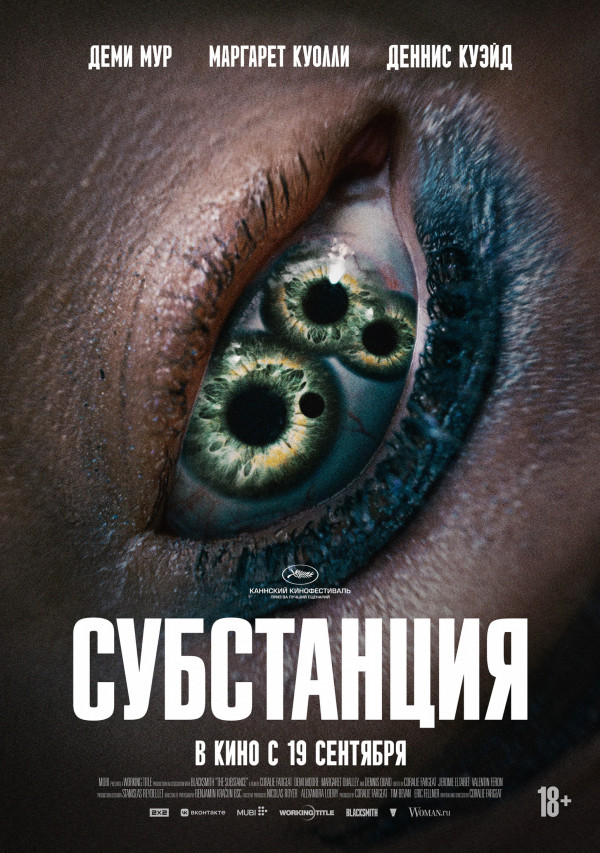

The Substance

The Substance is a sensational film – as good as it gets.

It has been a long time since I’ve encountered something like it. After watching The Night Porter and a few Brian De Palma films of late, I’d been lamenting that ‘they just didn’t make those sorts of films anymore.’

Apparently, I was wrong.

By coincidence, I had seen Coralie Fargeat’s previous film, Revenge, which I’d describe as a very nasty live-action cartoon confected of sex and violence. I have very little interest in films of that nature. Once the violence hits that hyper-real threshold, I can no longer relate to it. The storytelling function seems to switch off as the film descends into a pointless, abstracted spectacle.

Revenge is somewhat reminiscent of I Spit on Your Grave. That film stands as an example of exploitation cinema at its nastiest, and probably works as well as it does because of the profound shame and horror it evokes in a viewer. Revenge gives it a modern twist, turning the violence into an unabashed spectacle and tempts you to ‘enjoy’ it.

It’s quite remarkable to see so many of the same stylistic elements at work in The Substance, but turned to such a profoundly different outcome. The Substance is a very simple story in many ways, but that simplicity seems derived from the director’s profound understanding of the metaphor she’s spinning.

In the same way that Kafka’s Metamorphosis is an entirely modern story that has emerged from the chrysalis of its context, so too is The Substance. In fact, it could not be told in any other medium than film, because only with the complicity of screens has the body been able to change into the landscape it has become.

Fargeat draws on the various elements of the cinematic apparatus for fetishing the human body and questions what it means to make that body hyper-real, in all its shiny, glossy, contoured hyper-intensity.

There are some things that cinema does well, and it certainly creates a hyper-reality through the technology of sound and cinematography. Some theorists have likened it to the dream state. A film doesn’t have to make narrative, causal sense; in these terms, The Substance is at its most powerful.

It has the profound resonance of a parable or a fairy tale but updated for a modern context when injecting bovine toxin into your face to get rid of unwanted wrinkles and collagen to alter the shape has become so common as to be considered banal.

I kept waiting for Fargeat to lose control and for the story to devolve into a rip off of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde or possibly Metamorphosis, losing its unique poetic impact. I believe – and I’m willing to go out on a limb and say it – that Fargeat has produced a work that is as strong as either.

In some ways, I suspect it’s a film that a man can’t fully understand. It’s a film for women, I think, who have experienced disordered eating as a consequence of having their nature so polarised by the need to be perfect in order to feel loved, that everything believed to be ‘unlovable’ is then driven into a ghetto of the mind and gorged on darkness.

The story is a creative writing teacher’s wet dream. It continually sets up expectations and then violates them spectacularly, taking the story in directions that are completely unexpected, but feel completely right.

It continues to winch you upwards until the catastrophic ending, which you just know is going to happen, despite the caveats; after all, rules for safe conduct are only ever provided in myths and fairy tales so they can be broken.

The Substance is profoundly disturbing and very violent, not only in its depiction of gore and brutality, but in the entire style of the film. You actually felt as if the whole thing had been thrown at the screen, rather than simply projected.

At climax, the film explodes into an extraordinary pageant of sex and violence, cohering around the spectacle that is the human body. This incredibly powerful cascade of images and sounds delivers an ending that can only be described as apocalyptic.

However, the collision of beauty and ugliness, drenched in blood and fluid at the film’s climax (trying not to give anything away here) reminded me of a quote from the abstract sculptor, Ellsworth Kelly:

‘I think that if you can turn off the mind and look only with the eyes, ultimately everything becomes abstract.’

In the case of The Substance, that abstraction carries you into the realm of pure meaning.

For my money, I think Fargeat has taken film to the farthest possible extreme to which it can currently go. A couple of people actually walked out of the session I attended. I thought audiences had been desensitised beyond that.

Gloriously, she has proven me wrong.

Related

This entry was posted on October 6, 2024 at 4:40 am and is filed under Film, Pretensions toward cultural theory with tags Brian De Palma, Coralie Fargeat, Demi Moore, Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, Ellsworth Kelly, Franz Kafka, horror, I Spit on Your Grave, Margaret Qualley, metamorphosis, Revenge, surrealism, The Night Porter, The Substance. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

Leave a comment