Carldav13 Writes:

‘I reckon Terry Real got it wrong.

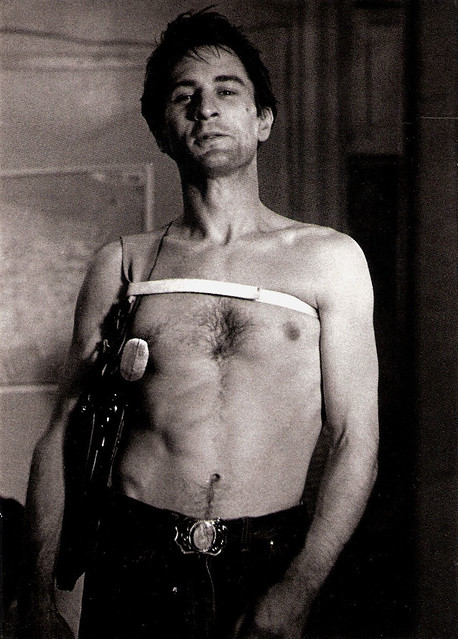

‘When I saw Taxi Driver, I thought that scene doesn’t make viewers laugh the first time they see it. I think it’s more uneasy like he looks clearly unstable and like his muttering and posture I thought was meant to reveal isolation and paranoia if I did laugh it would be more nervous discomfort rather than recognition of a braggart I don’t really know what that means…’

‘And for the deranged Narcissus part I think [Travis] is really hateful towards himself and almost suicidal to go on that mission at the end he’s imagining a confrontation in the mirror and preparing for violence it’s less of a self love to me more a delusion…’

‘Also it’s “You talking to me? [not ‘You looking at me?]

‘That’s my humble opinion.’

In response, the editor sent a section of the chapter of Real’s book, ‘I Don’t Want to Talk About It: Overcoming The Secret Legacy of Male Depression to Carldav13 for his delectation.

Carldav13 replied:

‘…it’s a bit much for me… when he says Narcissus brings his lips near to take a kiss I don’t reckon a guy with depression is gonna be metaphorically trying to kiss his own reflection. It just sounds like [Real is] trying a bit hard to be poetic instead of actually explaining something real.’

‘Some of it lands like the toughness aspect hiding behind pride and coldness sounds more real reminds me of Tony Soprano but the Narcissus far-fetched stuff loses Carl a bit…’

**

Dear Carldav13,

Thanks for your considered and incisive commentary. All of this blog writing has a ‘message in a bottle’ quality to it, and it is most gratifying when someone engages thoughtfully, as close-by as one of the neighbouring islands.

I think your observations about Taxi Driver constitute an astute reading based on the components Martin Scorsese, Robert De Niro and Paul Schrader have put in the box. However, Terry Real is reading Taxi Driver in a different way, and the comments I included on my Insta are some of the more provocative aspects of his thesis. I published them precisely for this reason.

I was motivated to read I Don’t Want to Talk About It: Overcoming the Secret Legacy of Male Depression after hearing Real speak on a couple of podcasts. I first came across him on The Tim Ferriss Show, episode 810, published on May 9 of this year. I was so impressed that I pursued his other appearances, and found him on The Drive with Peter Attia, episode 119.

Real said something on Attia’s podcast about the continuum between shame and grandiosity that the depressed man runs along, and how this has formed ‘the plot of every Hollywood action film made in the last fifty years.’

For yours truly, this was a lightning bolt moment.

In his book, Real goes on to say:

‘This theme of male transformation hearkens back to our archetypal heroes, like Odysseus, Orpheus, Siddhartha, and Jesus. As mythologist Joseph Campbell elaborated, the hero’s journey usually leads from some difficult trial, involving pain and humiliation, through an experience of transformation to a triumphal return.

‘Throughout most cultures and most ages, this mutation from a state of helplessness to sublimity has been affected by a spiritual awakening. In modern Western mythology, the same transformation is most often effected through the forces of rage and revenge.

‘…these scenes of ceremonial injury [in Rambo, The Unforgiven, etc.] hark back to Dionysus, Mithras, Jesus, and other heroes of the great mystery cults. But for the spiritually rich heroes of antiquity, it is their egos, their ordinary selves, that are rent in order to give way to the sublime. In our modern version, the hero’s self is not transmuted by spirit but inflated by violence.’

p. 69

Instead of only reading what’s in the box, Real seeks to read Taxi Driver within the context of the culture that has birthed it, and uses the myth of Narcissus to do so. Greek myths have been passed from culture to culture over thousands of years because of their insight that can reasonably be described as clairvoyant, and it is in this way psychology and psychiatry have sought to utilise them. To suffer from Narcissism is not to fall in love with your own greatness; it is to fall in love with the illusion of it, which is symptomatic of a deep psychological injury.

One of the most influential films of the last century was Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch. It set a new standard for depictions of violence in film, as well as presenting a particularly striking iteration of this story.

While it sits within the Western genre, it is well described as an action film, in that it is built around action set pieces and the sense of kinesis they instill. This kinesis is more than an intellectual experience; it is a physical one, also. The Wild Bunch is the story of a band of outlaws operating at the close of the ‘old’ West, somewhere around the turn of the twentieth century, just before the First World War.

Leave a comment